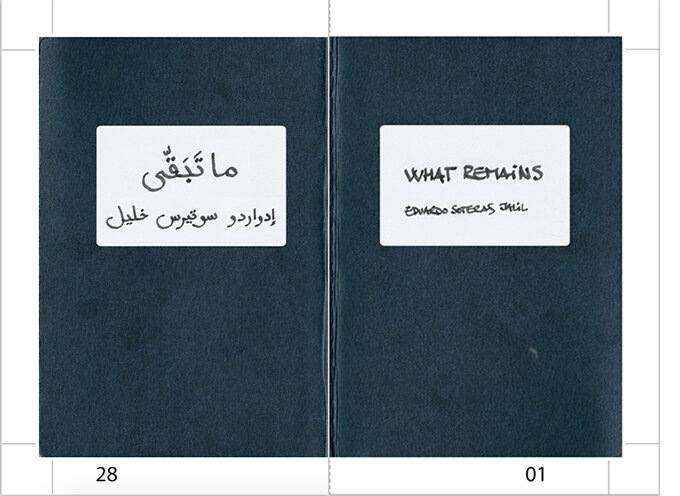

What Remains

Text for the exhibition of the project at Al Hoash Gallery, Jerusalem and originally published by Revista Anfibia.

For a copy of the text in Arabic, please click here.

The bad part about pain is that it hurts.

What's terrible is that war doesn't. It tears you apart, blows you up, it amputates, but it doesn't hurt. It turns into flesh, callus, fatty and scar tissue. It turns into something in your body, a part of you, but no, it doesn't hurt.

Pain, some say, starts off as a stimulus in a damaged part of your body (let's say, your foot), and rapidly reaches the brain, which takes care of translating that stimulus into something that you recognize as pain. Meanwhile, you pulled your foot free of that nail, you frowned, swore, checked for blood, and rubbed the injury.

War, in the beginning, and as a concept, definitely hurts. It starts when you take and make one yours, personal, familiar. No one summoned me – a young Argentine – to war, nor was I -a freelancer - invited or asked to take part: I simply made up my mind one day. Two days. A week. I might not even have decided on anything: it was that nail that was still there, bleeding and swearing, knowing it wouldn't leave me alone until I did something about it.

Still, I wanted to believe that one way or another I could escape the war, distract myself. I was in Gaza up until one week before the war, living that terrifying stillness right before the storm. For some time I had planned on taking pictures in Finland, and leaving felt like a sort of destiny, a form of understanding what I shoot, of defining myself: and the war starts and here I am, in a Finnish town, surrounded by a hundred thousand drinkers that sing and dance to something they call tango and that I've been wanting to document for years.

I returned to Israel, surrendering back to the place where I live. There was war, yes, but life around here went on as if nothing happened: bars were packed, folks shopped, the same films were being announced. It all went on like everything: sirens, flags everywhere, signs and posters with a lot of “victory”, “peace”, “we”, and an atmosphere as tense as a stadium full of angry hooligans.

In the meantime, Gaza remained there, slowly disappearing, humming with the F16's that flew near my faraway home, pounding like a waning rumor of bombings, that felt like someone else's nightmare in my own dreams.

Gaza quit being that familiar and frightening name for me, and a little over two months ago turned into proper nouns and faces I knew. It was a blow. It was very hot, humidity was oppressive, and everything needed to make a place livable was just absent. But still, it was a refreshing experience. It meant meeting people who, in spite of all things – inspite of everything there – wish to live and do things, they stand straight and stare at life in the face with eyes wide open, and embrace it will all their strength. In a very precise way, it sealed my return, understanding that Gaza was turning into a friendly face, a place of my own.

I insisted upon letting the war go by, tend to other issues, but the war wouldn't let me go. During those final days in July I went to the theater in Tel Aviv to see Hanoch Levin's “Requiem”, adapted from three stories by Chejov. For a moment, the war was only some guy at the beginning of the play announcing that, if sirens were heard, we were to go straight to the shelters. The play began and it seemed as if the war was far off, left behind. At one moment in the play, a desperate mother appeared on stage with a dying baby in her arms. Someone had poured boiling water on the baby and the mother was asking who could do such a thing to a child. Suddenly all those counts of dead children and shattered families immediately came to my mind. Gaza and the war then seemed further than ever, and all that emptiness and distance struck me in the face, and simply left me there.

So, it wasn't a decision, it was more like a need, a quest for relief. Covering the 56 kilometers from my home in Neve Shalon to Erez pass was an attempt at catching up on my sleep, coming to terms with so many absences. And right there, at the entrance door to Gaza, the pain ceased; perhaps the way it happens in our nervous system: the brain can translate it, but doesn't actually feel, nor can it feel, anything.

***

There are four of us in the apartment: two women – a French photographer, and a Polish journalist -, an Italian man who's a journalist, and me, Argentine.

The French and the Polish women have a two week lead over the Italian and me, and in war, that's a lot, almost like being a veteran, and perhaps that explained their condescending tone on many occasions. It's very easy, and very human to pick up that tone. All it takes is a couple of days of surviving bombshells and seeing people of all ages dead, to feel – believe – that you've come to understand something, as if there was actually something to understand in all this senselessness.

It's bizarre, but in wartime and all of its unpredictability, what keeps us going is a routine. We get up early each day, open the news and fumble for a way to turn the explosions that we heard during the night into the names of places and casualty counts. We discuss a path over a map that we'll use to tread through hell, watching it closely but without scorching our eyebrows.

Meanwhile, the door to our building starts to pack with cars that carry the letters “TV” on them. Cars sound their horns and in reply the building spits out journalists with helmets and bulletproof vests. There are hundreds of us in the building, from all over the world. Along this street on the sea front we're probably in the thousands, spread out over various hotels and apartment buildings. Right until before the war, these apartments were used by cooperation staff and volunteers, who will be back as soon as journalists leave the place. Hotels are always there, waiting for these kinds of moments when the city is filled with us. We are the closest thing to a tourist that the hotel workers can dream of.

Over here Gaza is friendly. The sea is very close by, streets under construction promise a certain comfort some day and there are certain unimaginable luxuries like electricity around the clock. In times of peace this street is an endless procession of marriages, of families who are out for a stroll, and of fishermen returning in their carts. Today, it's no more than a desert, roamed only by press vehicles and guys dressed up like robocop going in and out of hotels.

Over here, Gaza is also a place that could seem normal. There's water, people are properly fed and one way or another they manage to sleep at night. There are restaurants open and a certain naive peace of mind that things will remain intact tomorrow and the day after. Corner stores remain open with fridges that refrigerate – some even have bread – and the fresh water tank at the entrance shows a couple of people queuing up, not the hundreds you see in any other district in the city.

Our building's hallways are usually our best source of information, and there we exchange data about who is going where and in case of real danger we try to set up convoys. You can land in this place without the slightest idea of where to go or how, and it's just a matter of standing around and waiting for someone to take you or advise you.

Adapting here takes a while, although time here passes differently and bears another load. As days go by, they feel like weeks, and with every outing you start gathering sad and necessary knowledge: odors, sounds, colors. You start telling the difference between the smell of trapped and decomposing bodies, and the smell they have in the morgue, and from the color in the blast's cloud you can tell if the bomb hit a house or an open field.

Sounds are there every hour of the day. Wherever you are, you'll always feel the drones in your head, in your dreams, and little by little you'll recognize the different kinds of blasts. You learn that the loudest thunder belongs to F16 bombs, that drone missiles leave a surgical scar in the air, that tank artillery have a flanking sound and they're the ones you have to take cover from the fastest because they're so imprecise. You notice the rumble of shelling from the sea because it sounds twice, like an echo, and when it happens you get the sense that half the city is about to disappear, as if there still were half a city standing to gun down. You also learn to recognize the amplified bottle rocket sound followed by the exclamation “one of ours!” These are the home made missiles that are shot from Gaza, and the closer they are the faster you have to dash for shelter because it's about to get ugly.

In war, routine boils down to the same progression of sorrows each day: first, the bombed areas, then the hospital including the morgue, after that the funerals, and later back home for the editing. If there's a truce we'll go to spots inaccessible under fire to see how bodies and belongings are recovered, until the thundering lets you know that the truce has fallen, and you try to get home as fast as possible.

There are different ways of working in a war. A lot relies on a “fixer”, who is literally someone who sets everything up for you: contacts, interviews, translating, moving around with certain peace of mind in the roughest situations. Those that know the place and speak Arabic get around with a driver that takes them from place to place, waits for them, gives advice on possible routes and unsafe places but he doesn't interfere with the work.

We usually moved around with a driver, but during the first days there wasn't enough room for me in my roommates' car, so I ended up with a fixer, a guy in a mustache with a chicano English accent which he picked up during his years in Harlem. The work with the fixer, at least with this one, is the closest thing to a tour: he takes you to each spot without asking too much, he mentions the specific attractions and makes you see them, all for the meager sum of three hundred dollars per group.

I suppose that if you're short on time, or have gotten good at processing tragedy, it's a convenient way to work. We arrived at a bombed school, and he indicated where the blood was and who the casualties' relatives were. At the hospital he led us straight into the ER where those who just arrived still had open wounds, and if after that we felt like getting out of there he looked for us and reminded us that the bodies in the morgue were being prepped and that a special spot had been set apart for us so that we could take our photos. We insisted on leaving but he took us by the arm and led us to where the dead girl's father was crying in the intimacy of his family and dozens of photographers and journalists.

Something breaks in war, a lot breaks, and among the most important are limits. People are too beat up to understand what's going on, and it's easy, just so easy, to trespass on the grass of others' intimacy and then leave as if nothing happened.

***

Pain recedes as soon as you walk into war. Fear, of course, doesn't.

There's no way, it's just impossible to predict how and where fear will come from, what color it will have and what shape.

Fear is like expecting a child: so much hope, so much we envision, until he or she arrives to stay. They'll grow up, but in the best case, they won't leave your side.

I don't have kids, but I have fears. Tremendous ones, huge. Fears that built up over years and now cram all together: an organic fear, not of dying, but of ending up in parts. Or, after seeing so much death, I have a fear that a part of me is dying inside. I also have a professional fear of not coming up with a decent piece of work considering all the lives I trod on without permission; I am using so much tragedy as raw materials. A human fear of everything being left along the path, unfinished, so many promises to myself and to my people, so many things I've left half-baked, so many incomplete lists of trees, books and children.

Fear, real fear, is sometimes so great that it seems as if there were none at all.

The most honest, their hands shake, others' voices become acute, while many twitch their mouths or fix their hair: we're fear each and every one.

There are different kinds of fear. Fear of bombs is unique. It's a senseless, concrete and random fear. There's a blast nearby, and you never come to understand why the difference of only a few minutes since you passed that spot: you'd love to believe that you actually understand something about that, an order of some sort, but there's no such thing.

I got it on my first day on the ground. We headed out with my Italian colleague, Andrea to shoot a church where Shujaia families were taking refuge and on our way the horizon was covered in a black cloud and the streets were filled with people running our way.

Curiosity overcame us and we asked the driver to take us closer. We reached the crossing at an avenue and about a hundred meters away there were fire and bodies strewn on the street. Without time for second thoughts, we shouted at the driver to get us out of there. He didn't want to understand and instead of turning around he drove right into the center of the blast, and with a smile pointed to the bodies a few steps away. We shouted out again. We wanted out of there, but we were the very first journalists to arrive. After that, he started to back out. On the way out we crossed a Palestinian journalist who was just arriving. Rami Rayan, was his name. A few minutes later two more missiles landed and Rami died blown apart.

That takes place and then I keep on looking for an explanation, an algorithm. Sometimes I think it has something to do with technology. I imagine that if Google knows so much about me, then the Israeli Army must know as much, too, and I want to believe that when my Israeli cell phone is switched on there might just be a red dot with an Argentina flag on some cynic's screen who waits a second before pushing the button, deciding who lives and who doesn't. I mean, I wish.

I also think – or I want to think – that a lot is about luck, and if you believe in luck you come to realize that in war it's cast from the moment you arrive. Gaza is a place with nowhere to hide and any feeling of a safe place could be your last. You come to think that being brave is when you no longer care about anything, in a way its about giving up. Bombs do that to me, they wear me out.

What has scared me the most these days was the idea of having to go to the dentist: I visited him right before leaving for Gaza and the guy struggled for an hour trying to pull out an implant. He failed. It hurt.

Sure, it sounds tough and daring. But if you think about the bombs everything makes more sense: bombs are like planes, if they fall it's game over, goodbye. Driving back to the dentist – with the physical suffering, paying him and arranging for another appointment – it's an entirely masochist act, premeditated, too certain.

***

On our apartment's couch, Ahmad, who demands being called Johnny, lies asleep. Thin, electric, with an iphone 5 that won't stop ringing. I met him a few months ago in the preface to the war, at a time when, to enter Gaza, you needed to נe endorsed by someone who would follow you around and tell Hamas what you were up to. He endorsed me, understanding that I didn't have a penny,and that I wasn't on the hunt for news or contacts. We became friends.

Johnny, or Ahmad, has found a bizarre opportunity in the war. He finally got to work. Many are in the same situation: people with a certain education, a car in working conditions, and decent enough English that will open one of the many sealed doors. They work as fixers under fire, because it's their only option.

Mark, our driver, is a catholic from Bethlehem who was expelled to Gaza after a few years in an Israeli prison under charges he still doesn't know. Gaza to him is ostracism. In Palestine, arriving to a place with no family ties (and the connections they imply) is a sort of punishment, death in life. Mark has fluent English, a university degree, a wife and two kids he hasn't seen in four years. His only option is to spend his days driving to places that have been or are about to be shelled, carrying poorly paid – sometimes unpaid – journalists, that pay him twenty dollars an hour.

There's a schizophrenic blend to all this: A blend between people that have no other option and those that do. Do we do the work out of certain principles? ideals? curiosity?; we are freelancers who nobody has asked (nor ever will ask) to be here, and much less will anyone ever pay us?

Why, then? My friends in Gaza do it because they have no options. In our case I want to believe it's due to an obsession of some kind, something that keeps us pressing down on the camera's shutter and the computer keyboard, a desire to tell about what shouldn't be happening.

The camera and the writing perhaps promise a sort of salvation. A standing on the sidelines from where we can watch everything with a certain anthropological detachment. We are one notch up trying to reach the cupboards that hold that challenge of explaining man to man.

Well, it's not for free. It never is.

My friend Alice arrived right after the war had started, staying for twenty-five endless days. Today, back in France, she still has flashbacks and nightmares. She remains anxious, still staring at the sky in search of drones and every time she hears the sound of a plane she gets startled. She insists: she wants to get better so she can return to Gaza and continue working.

A few days ago another colleague died. Simone died while filming the work of the police anti-bomb squad trying to deactivate a bomb. I didn't know him, but it disturbed me the way it disturbs all of us who have been there. Death, it's imminence, draws us closer, and befriends us without warning.

On the day Simone died many of us started texting trying to figure out who had died, where, what was going on. Oscar, who I crossed in Gaza for only a few minutes, which was more than enough to become friends, wrote me “they showed me the guy's face at the morgue, and I felt a knot in my throat, because the dead always seem to stare at you, not to be dead. A person's impression when seeing another, can't understand death. We don't fully grasp that we are frail, so very frail. It's a damn shame and I didn't even get to meet him”.

We translate the pain, we explain it without feeling it, but we recall it when we forget how frail we are.

War is a pain that becomes an instinct. A rank, metallic, foul taste. Something that remained trapped after clenching your teeth while shooting so many photos among the dead. A piece of debris, some muck that got stuck in your implant, that you can't pry loose, although you realize, it rots away little by little.